Artist and co-founder Bose Krishnamachari has resigned as president and trustee of the Kochi Biennale Foundation, citing pressing family reasons. His exit comes during the ongoing sixth edition of the biennale and signals a significant leadership transition for the influential cultural institution, which has begun the process of appointing a new president.

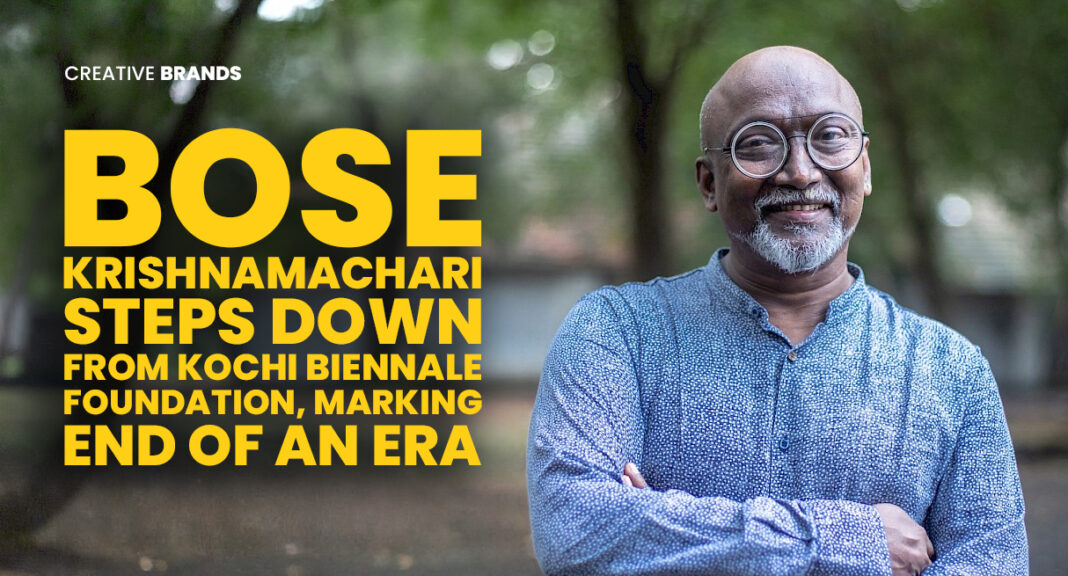

Artist and curator Bose Krishnamachari has stepped down from the Kochi Biennale Foundation (KBF), marking the end of a defining chapter in one of India’s most influential contemporary art institutions. The resignation, tendered on January 14, removes Krishnamachari from both his roles — as president of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale and as a member of the KBF Board of Trustees — positions he occupied since the biennale’s inception. According to a press statement issued by KBF chairperson Venu Vasudevan, the artist cited “pressing family reasons” for his decision to withdraw from active leadership. The announcement, succinct and formal in tone, also underscored Krishnamachari’s foundational influence, noting that he “has been one of the most influential figures in the growth and evolution of the Biennale.” For many in the global art circuit, the news represents not merely a routine administrative transition but a symbolic shift in the journey of an institution that has reshaped India’s cultural landscape over the past decade.

Krishnamachari co-founded the biennale in 2010 with fellow artist Riyas Komu. Their shared vision — to create a world-class biennale in India’s southern coastal city of Kochi — seemed audacious at the time. India had no precedent for a large-scale contemporary arts biennale, nor for the type of international curatorial and participatory formats that define similar events in Venice, Berlin, São Paulo, or Havana. That early scepticism was gradually replaced with admiration after the first edition opened in 2012, drawing artists, critics, collectors, students, and ordinary visitors into warehouses, godowns, colonial buildings, and repurposed heritage spaces scattered across Fort Kochi, Mattancherry, and Ernakulam. Over the years, the biennale grew not only in scale and attendance but in ambition, shaping conversations about art practice, public engagement, cultural policy, and South Asian agency in global art discourse.

Krishnamachari’s exit comes as the sixth edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale unfolds across the city. Titled “For the Time Being” and curated by performance artist Nikhil Chopra in collaboration with HH Art Spaces, this edition opened on December 12, 2025, and will run until March 31. It arrives at a moment when biennales globally are grappling with questions of sustainability, ethical representation, financial precarity, and local participation. For Kochi, the current edition has also been closely watched for how it would reassert post-pandemic cultural momentum and reconnect international publics with India’s contemporary art ecosystem. Against this backdrop, the resignation inevitably sparked speculation about its timing and implications. However, for now, the official line remains unchanged: the reasons are personal and familial, not institutional.

Still, Krishnamachari’s departure invites reflection on the broader arc of the biennale’s institutional history. Over the years, his leadership was both celebrated and critiqued. Admirers emphasised his persistence, networking, and uncompromising vision that secured Kochi a place on the international art map. Others debated issues of governance, transparency, and curatorial authority. These tensions are not unique to Kochi; biennales worldwide operate at the intersection of public culture and private patronage, constantly negotiating artistic freedom, administrative oversight, and community endorsement. Krishnamachari often functioned as the fulcrum of these competing forces — a role that demanded both charisma and negotiation, traits he was widely acknowledged to possess.

The press statement announcing the resignation also noted that the foundation has initiated the process of identifying an “eminent person with high credentials in the art world” to take over as president. In practical terms, this transition will shape decisions about future editions, international partnerships, educational programming, and the long-debated prospect of establishing permanent art infrastructure in Kochi beyond the biennale’s exhibition cycle. One of the foundation’s recurring challenges has been managing the discontinuity that accompanies the event’s episodic nature — every edition builds intensity and global visibility for a few months before the city returns to its everyday rhythms. Leadership transitions, therefore, carry significant implications for sustaining institutional memory and strategic continuity.

For the art community, especially within India, Krishnamachari has been more than an administrator. Born in Kerala and trained in Mumbai, he developed a sensibility that blended global exposure with regional rootedness. His practice encompassed painting, installation, curating, and pedagogy, and he frequently operated at the overlap of these modes. Before the biennale, he was known for energising Mumbai’s contemporary art scene in the 1990s and 2000s, organising exhibitions and dialogues at a time when the city’s art infrastructure was undergoing transformation. The biennale, however, amplified his role from a national figure to a global cultural interlocutor, drawing attention not only to his own trajectory but to Kerala’s positioning within transnational artistic networks.

The other co-founder, Riyas Komu, had stepped away from the organisation earlier, leaving Krishnamachari the sole original architect within the foundation’s leadership. His resignation now completes a generational turnover. What the next phase looks like — structurally, curatorially, financially, and ideologically — remains a matter of anticipation. For many younger artists who made their first significant public appearances in Kochi, the biennale functioned as both a launchpad and a narrative counterweight to Euro-American art circuits. It offered visibility without demanding migration; it allowed experimentation in formats that might not find space in commercial galleries; it involved local communities as participants, collaborators, and, at times, critics. Change in leadership could recalibrate these dynamics, for better or worse.

Meanwhile, on the ground in Kochi, the current edition continues to draw visitors. Chopra’s curatorial lens emphasises performativity, time, and embodied presence, inviting viewers to encounter art not as a static display but as an unfolding encounter. The thematic choice resonates with the fluidity and transformation that biennales often evoke. Ironically, the title “For the Time Being” now acquires an unexpected institutional subtext — a reminder that even cultural infrastructures, like artworks, operate in temporal frames, subject to shifts and exits. Whether intentional or coincidental, the overlap between title and timing adds poetic complexity to the moment.

Within cultural circles, early responses to Krishnamachari’s resignation ranged from gratitude to curiosity. Several social media posts and informal statements described his departure as “the end of an era,” while others expressed confidence that the institution would reinvent itself. In India, where public arts funding remains limited and state-supported cultural institutions often move slowly, the biennale model has always been somewhat fragile. Its survival depended on a network of donors, governments, artists, volunteers, and civic bodies. Leadership mattered not only symbolically but materially — in fundraising, advocacy, diplomacy, and long-term planning. Whoever succeeds Krishnamachari will inherit these responsibilities but will also encounter new expectations shaped by a more globally networked generation of artists and audiences.

For now, the foundation has chosen continuity over disruption, emphasising that existing programming and the current edition will proceed without alteration. The immediate focus remains on sustaining the biennale’s public engagement through March. Beyond that horizon, the art world will watch closely as the foundation names a successor and outlines its next decade of ambitions. The biennale is no longer an experiment; it is an institution, and institutions outgrow their founders. Yet founder departures always carry emotional weight, especially in cultural movements built on personal conviction and collective imagination. Kochi’s biennale was both.

In the end, Krishnamachari leaves behind not merely an appointment but an era — one that altered India’s contemporary art landscape and inserted Kochi onto the world map of biennales. Whether history will view this resignation as a quiet administrative moment or a turning point depends on what comes next. But for the time being, the biennale continues, the artworks and performances unfold, and the city remains the stage on which the next chapter will be written.

Discover more from Creative Brands

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.